Introduction

The UK is in the process of switching to an all-digital (IP-based) telephone network, with significant operational and strategic implications for telecare alarm services. This switch-over presents an opportunity for the sector to be reimagined through digital transformation and the integration of technology-enabled care (TEC) and support services. It has the potential to support new opportunities for an expanded role for care technology applications and services, with an increased use of data to realise improved outcomes for service users and commissioners. This will open the market for the many new entrants in this sector that are offering innovative data-rich products. These will be competing against established mainstream suppliers that are currently focussed on producing digital equivalents of their legacy analogue units, essentially replicating their features.

The sector is therefore at a crossroads – alarms vs data; however, change can be hard and difficult for risk-averse organisations who favour established service models and technologies over newer, less proven approaches. But there is also a risk in not changing. Focussing solely on replicating analogue TEC services would represent a missed opportunity, and a potentially expensive one at that. As people become used to smartphones and other digital consumer technologies in their everyday lives, the perceived value of a traditional alarm service, that they might use rarely, may decline. This could lead to a reduction in the number of service users, currently estimated at 1.7 million in the UK, when it should be growing to meet the needs of a wider range of people, using new technologies, and to support the needs of an increasingly elderly population.

This article is a prelude to a series we are writing over the next few months focussing on the changes and challenges facing the Technology Enabled Care sector, and social care in general, in the UK, and how commissioners and service delivery organisations will have to change their ways of thinking to offer a better way of providing support.

We begin by presenting a brief history of the sector in the UK – from its origins in community or social alarm systems to the more contemporary telecare services commonly in use today. This is to understand why telecare services look like they do, and how their evolution for the digital world will not simply be realised by changing the technology but on how services are re-designed around it.

Social and community alarm systems

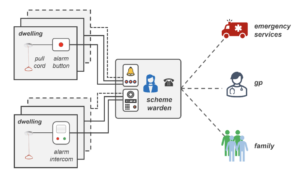

We begin with the decade following World War 2 which coincides with the formation of the NHS and an increased attention to the welfare of millions of people who had lost their homes, their loved ones, or their livelihoods. But it was a time of great hope for the future and a widespread desire to reject the workhouse and other symbols of an unfair past. Local authorities were given the responsibility to rehouse the nation’s heroes and its older people; they built sheltered housing apartments and bungalows. These were often serviced by scheme wardens who lived on-site, and who could provide support when needed. The systems were basic; tenants had pull-cords, usually in the bathroom and next to their beds, that were hard-wired to the warden’s office. These could be used to summon the warden in the event of an emergency at any time of the day or night, 7 days a week. They originally featured a simple bell, but alarm-panels were eventually introduced. More sophisticated arrangements appeared over time with intercoms that enabled tenants to speak with their warden or with visitors who needed to be admitted to a scheme. Figure 1 shows a schematic of this simple arrangement with typically dozens of hard-wired connections. The limitation was the availability of the warden who needed holidays and might be off sick; they could only attend one alarm at a time with no mechanism for prioritisation.

Figure 1: Simple community alarm system for schemes.

The systems were popular because, at that time, few older people could afford to have their own landline telephone; these alarm systems offered them a convenient way of contacting their GP, the emergency services, or their family when in need. Over time, the residential warden role became redundant; posts became difficult to fund, leading to a need for visiting servicesfrom mobile wardens.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of older people lived in dispersed housing and had their own telephones. In 1974, Andrew Dibner, a U.S. psychologist and academic, and his sociologist wife, Susan, invented a medical alert system called the Lifeline. It was based on a unit that had a radio receiver that could be activated by pressing a wireless pendant radio transmitter worn as a lanyard around the neck. In a hospital or nursing home, this would be linked to the nurse’s station. But a new generation of Lifelines was developed that plugged into the telephone network so that they would connect remotely to a 24/7 support network. Thisled to the creation of ‘control’ (monitoring) centres, the first of which in the UK opened in Stockport in 1979. Within 20 years, they had sprung up across the UK, with nearly all district councils in England (and local authorities in Scotland and in Wales) having their own centre from which they could manage calls using the arrangement shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: A typical community alarm system from the 1980s.

It remained a relatively simple system but with more options both for actively raising an alarm and for having a timely and appropriate response as decision making moved from the schemes to the monitoring centre. The centre could manage hundreds, and often thousands, of connections that were fielded by a team of call-handlers. It can be considered to be the first generation of telecare.

Care in the community

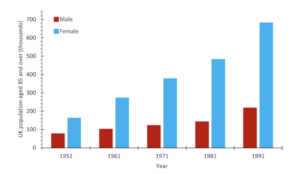

The number of older people in the UK increased rapidly during the second half of the 20th Century. In particular, the number of “old, old” i.e. those aged 80 or over (and deemed most like to be at risk of ill-health and accidents) increased by over 30% each decade from 1951, Figure 3.

Figure 3: The growth in the number of people aged 85 and over in the UK from the 1950’s to the 1990’s*.

Many of these people, especially those who lived alone, ended up in residential care homes funded by the Department of Works and Pensions. When funding transferred to local authorities as part of the Care in the Community changes in the 1990s, there was a new focus to help keep older people in their own homes for longer. This led to a rapid expansion of homecare services but also a realisation that community alarm services could also play an important role in avoiding long-term care, and especially for people who lived alone or had no close relatives who could look in on them every day.

Technologies matured with a new focus on improving the quality of services at all levels, but especially for those people who didn’t live in sheltered housing schemes and for whom there was no warden service to identify issues that could quickly be resolved.

Local authority assessments of need often resulted in some home help being provided to help with domestic tasks such as light cleaning, laundry services and collecting groceries. It was often accompanied by a referral to a community alarm service. The areas of greatest concern were the possibility of someone falling and having a long lie on the ground, security issues (often related to bogus callers or the failure to keep the door locked), and forgetfulness, which could lead to flooding, cooking appliances being left on, or someone leaving home during the night and failing to return home. For various reasons, e.g. a reluctance to always wear a pendant, these incidents were generally not reported until it was too late. This led to the idea of passive monitoring using smart sensors – and the creation of a second-generation of telecare.

Wireless alarm pendants were used with an extended range of smart sensors, such as the prototypes shown in Figure 4, to detect many different environmental and social emergencies. These devices were introduced during the first few years of the 21st Century and commercialised mainly through Tunstall, the market leader, following their acquisition in 2001 of Technology in Healthcare (TiH), whose range of innovative smart telecare sensors had been awarded ‘Millenium Product Status’ from the Design Council.

Figure 4: Examples of prototype smart sensors used in second generation telecare systems in the 2000’s.

The prototype devices were used in major pilot projects in West Lothian, Northern Ireland, in County Durham and in Cheshire. They included a worn fall detector, bed occupancy sensor, a property exit sensor, an enuresis sensor, a flood detector and a temperature extremes detector. The commercial versions became the backbone of the products often funded through the Preventative Technology Grant and its equivalent in the devolved nations between 2006 and 2008.

These second-generation telecare systems ‘piggy-backed’ on the established platforms as shown in Figure 2 but supported enhanced decoding at the monitoring centre to identify the device and the alarm type/reason. Some devices could signal different alarms or states, enabling the most appropriate response to be initiated. This approach flourished for over 10 years during which time the assessments and the support available matured. Services were able to establish protocols around the process shown in Figure 5. This worked well to manage the risks associated with many types of emergencies from environmental concerns, such as fire, flood and gas, through to more social issues such as falls, medication mismanagement, security, bogus callers and for people with cognitive impairments.

Figure 5: The processes employed to operate an effective telecare alarm service.

This approach was based on the need for effective assessment of risks which could then be managed through rapid detection and response. In most cases, sensors were provided only for those people who had already experienced an accident and to those who were housebound. Service quality improved significantly but failed to prevent the incidents that led to A&E admissions and the need for long-term care. As charges to service users were increased to cover the cost of providing services (coinciding with the removal of subsidies from schemes such as Supporting People), many users failed to perceive the value in their ‘just in case’ alarm service, especially if they hadn’t had any cause to use it. The large-scale adoption of smartphones and the introduction of specialist mobile alarm devices that extended the ‘safety net’ outside of the home also highlighted the limitations of home based solutions. Home-based telecare moved into a new phase where data was collected and used to predict future decline, enabling measures to be implemented that could prevent falls and other accidents from occurring, i.e. a third generation of telecare. These systems have been available for several years, with some success, but are struggling to displace the incumbent alarm-based model as the primary approach to providing technology-enabled care.

The digital age

Over the past decade, there have been major technology developments in:

- smartphones and apps

- home broadband, mobile connectivity and low power wide area networks (LP-WANs) • mainstream consumer smart home devices and in-home wireless connectivity • sensors and devices such as wearables and the Internet of Things

- battery technology

- voice-based user interfaces and intelligent assistants using ‘AI’ (e.g. Alexa, Siri) • cloud computing and ‘software-as-a-service’

- data analytics, visualisation, algorithms, and machine learning

The story of telecare is one where services have been built around the needs of the user but constrained by the capabilities of the available technology. This has resulted in the dominance of a reactive service model that helps individuals if they, or smart devices, raise an alarm following an adverse incident.

As digital technologies become more mainstream, the range of needs that can be supported using technology will increase and the nature of that support will also move away from solely focussing on alarms. It follows that to maximise the impact of these improvements in technology, the services built around them must also be re-designed to reflect this. Significantly, the role of the monitoring service (or centre) will change as services move away from a solely reactive alarm-based ‘just-in-case’ approach to a more versatile and preventative data-rich ‘just-enough-support’ approach. The focus on specialist alarm products will also be challenged with greater adoption of consumer devices, that are often cheaper and more aesthetically appealing, removing the ‘badge of dependence’. The future promises a technology-layer in the home, and on the person, that supports the concept of ambient assisted living.

These changes will present numerous challenges to the sector. These will primarily revolve around the shift from an alarm-based service to a data-monitoring service. At a high-level, once useful information and knowledge is available, the need to be able to share this across relevant health, care and housing organisations will grow. This will require a level of interoperability not previously seen across the sector – from the development of common data standards on how activities of daily living are classified through to the recording of outcomes. This will be required to support the integration of data from products produced by different vendors. It should also be the case that the end-user will maintain the right to choose which data are shared and who it is shared with.

Other challenges will be the mix of specialist vs consumer technologies, how people are made aware of, and supported with, these new digital products, and to ensure data protection and security is assured across the whole platform. There will also be a significant change in the role of staff, including in the monitoring service. This will require additional training and resources to provide them with the knowledge and skills required.

The future of technology-enabled care is an exciting one; but these challenges will need to be addressed if it is to thrive and offer a better future with more hybrid arrangements of support.

The topics presented here will be discussed further in subsequent articles in this series.

Article written by T-Cubed

*Census data.